Note: for the sake of posterity, and because I’ve been blogging long enough to know that online stories tend to go missing after a while, I’ve started trying to repost articles in which I’m included. This lovely post by Ellen Shapiro, who came to see us at Pencil to Pixel, originally appeared on Print magazine’s site.

At Monotype’s “Pencil to Pixel” pop-up exhibition in New York City last month, 3,400 students and professions learned about the history of typography. Artifacts demonstrated how metal type was historically designed, made, specified by designers, and set by typesetting companies — and translated into today’s font menus for individual users.

“The lesson from an exhibition like this is that the design of a typeface can outlast the moment that produces it, and that a good design can evolve to meet the needs of technology without losing its essential spirit,” said Dan Rhatigan, Monotype’s UK type director. “Lots of younger designers who came through seemed really eager to see the background of the typefaces they already know, and the exhibit helped them appreciate why we’re still trying to improve the technology behind those designs,” he added.

Here are close-ups of some of the artifacts that were on display as well as some typography history:

1928 — Eric Gill’s pencil and ink drawings for Gill Sans, the fifth best-selling typeface of the twentieth century. Gill (1882-1940), a British sculptor, stonecarver, printmaker and typeface designer, designed Gill Sans in 1926-1928 for Monotype at the request of Stanley Morison, who was interested in a contemporary sans serif face with British character. Classified a “humanist” sans-serif face intended to be legible in both display and text, its proportions were based on Roman letterforms rather than being constructed geometrically. Famed uses of Gill Sans include programs for British Rail, the London Underground, Penguin Books, Saab Automobile, and the BBC. Note the use of white gouache paint to touch up the letterforms.

1937—Copper patterns for Eric Gill’s Joanna. Copper pattern plates were utilized in the manufacturing stage between the drawings and the metal type itself. A transitional serif typeface named for one of Gill’s daughters, Joanna was designed in 1930 and originally intended as a proprietary face for his printing business, Hague and Gill, opened in Buckhamshire, outside London, with son-in-law René Hague. It was adapted by Monotype in 1937 and made publicly available in 1958. Gill set the text of An Essay on Typography, his classic book on letterforms, typesetting and page design, in Joanna. In the book, he demonstrated and championed the first use of “rag right” rather than justified columns to create even letter- and word spacing.

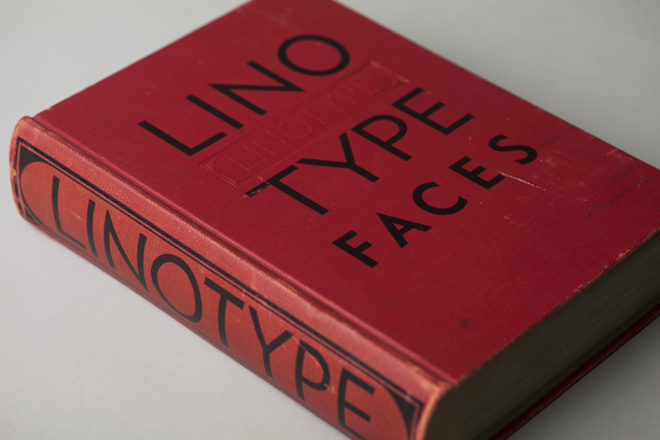

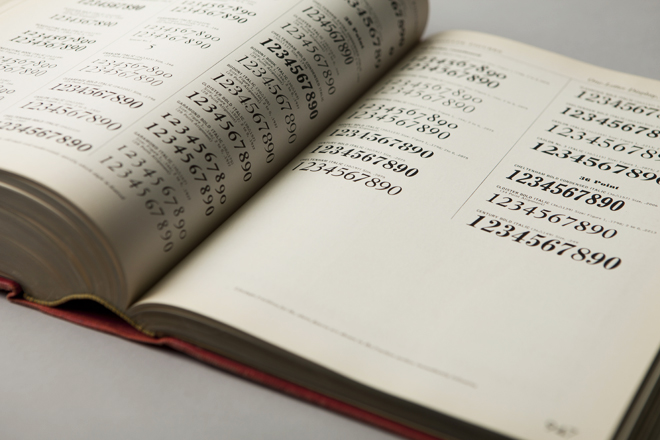

1939—“Big Red,” a comprehensive specimen book of Linotype faces. Published by Mergenthaler Linotype Company, this classic reference tool measures 7.75″ x 10.75″ and contains 1,215 pages of type specimens for hand-set headlines and text set on linotype machines, including model ads and announcements with lavish use of dingbats, ornaments and borders.

1932—Littleworth. These rare, original letter drawings are in the Monotype archive for Littleworth, a hot-metal typeface no longer available,

1971—Classic linotype faces were remastered for photo-typesetting. These brochures announced Monotype newly released versions of Helvetica and Univers for use on the first photo-typesetting machines.

1980—The ITC Typeface Collection, a specimen book of the library of the International Typeface Corporation. This 574-page, 12 x 12” square book is a compendium of the individual “26 Good Reasons to Use” booklets originally designed by Herb Lubalin and released by ITC throughout the 1970s. It was published to interest manufacturers of typographic equipment and materials in licensing the ITC typeface library, which included American Typewriter, Avant Garde Gothic, ITC Benguiat, ITC Bookman, ITC Century, ITC Franklin Gothic, ITC Garamond, Korinna, Lubalin Graph, Serif Gothic, Souvenir, and Zapf Dingbats. In addition to Herb Lubalin, type designers included Ed Benguiat, Tom Carnase, Tony DiSpigna, Aldo Novarese and Herman Zapf.

The book concludes with a copyfitting chart, essential to all designers, part of whose job was to mathematically convert typewritten manuscripts into set type by calculating the size and leading to fit on the page.

In 1980, ITC subscribers included Cello-Tak, Chartpak, Letraset and Zipatone, manufacturers of rub-down lettering, in addition to Alphatype, Berthold, Compugraphic, Monotype, and other purveyors of photo-typesetting equipment. Agfa Monotype acquired ITC in 2000.

2013—the typographic body art of Dan Rhatigan, Monotype’s UK-based type director. This was the “display” in the exhibit I was most curious about (even though he was standing next to a display of covers and spreads of U&lc, a few of which I’d had a hand in).

“My tattoos are always a point of interest with type crowds,” said Rhatigan, who said he got his first tattoo, the swashy ‘R’ of an ersatz family crest he designed, in 1998. “After staring at that ‘R’ for months, I realized that my love of type is timeless. So I started adding shapes I loved from different typefaces, working with different tattoo artists who appreciate the idea enough to carefully reproduce the artwork I supply.”

Rhatigan’s friend Indra Kupferschmid put together a custom MyFonts list of most of the typefaces that are tattooed on him. There are a few others, too, he added (some of which apparently can’t be shown in polite company), including letters from Delittle Wood Type foundry; from H&FJ’s Champion Gothic; and from Sodachrome, designed by Rhatigan and Ian Moore for House Industry’s Photo-Lettering collection.