Working draft #2:

I have always done my best work when I have been able to understand a problem or a task by engaging myself with the ideas underlying it, tinkering and exploring possibilities. The scope of a issue, the plastic qualities of a particular material, the aesthetic sensibilities of a client or an audience, intriguing subject matter investigation of any or all of things is crucial to my ability to enjoy and succeed at what I do. This principle that has guided me through my career so far, informing my decisions to accept or discard various challenges on the basis of their ability to nurture my desire to learn as I work.

As an art student at Boston University, I learned not to produce artwork, but to think of its practice as a way to explore anatomy, history, perception, composition, and the pleasures of various media. Eventually, the study of graphic design led me to typographic expression and a practice of problem-solving that left room to draw upon the full range of talents at my disposal. Studying design in the early 90s also exposed me to digital technology at a time when I would be able to explore it as my profession was fundamentally altered by it.

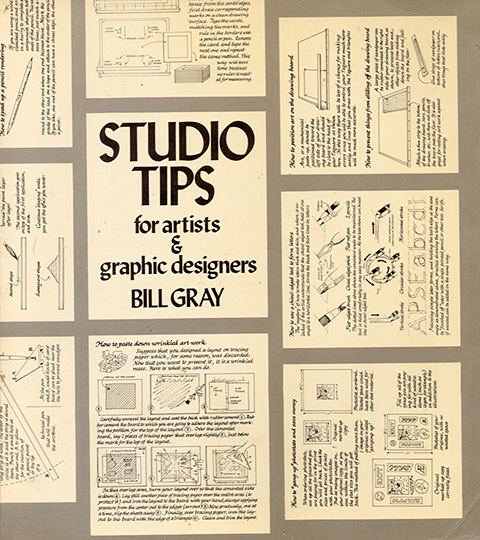

Shortly after graduation, I took a job as a typesetter with the university, viewing it as an apprentice-ship in the finer points of typography and printing. (Fortunately, it also gave me a way to take more classes without the burden of tuition.) The digital aspects of that job also began my career in publishing technology, which has competed with graphic design as my primary focus ever since. When working as a designer neglected to feed my curiosity and desire to learn continuously, then working in technology gave me opportunities to explore other ideas altogether.

To me, the connections between the two fields were obvious: both addressed the need for clarity, communication, and ways to address current goals while planning for those that may develop in the future. Craftsmanship, investigation, and originality are intrinsic to both. Inventive solutions to many design problems often depend on the use of technology, and vice versa. In the workplace, though, organizations are often structured in ways that encourage discrete rather than cross-disciplinary activity, despite the limitations of doing so.

Tired of ricocheting between disciplines to feed my expansive curiosity, I began working toward a master’s degree in communication design at Pratt Institute. Before my first year in the program was complete, I realized that the experiment was a dismal failure. Rather than a source of guidance and criticism an environment that would allow me to develop the connections I saw between graphic design and the systems that support it, and how each could enhance the other the program proved to be more appropriate for students looking to perfect particular professional skills. Facing conflicting demands of work and school, I chose to abandon basic courses that repeated the lessons of my undergraduate studies in favor of the few classes that let me grapple with complex design problems. When I withdrew from the program, those incomplete courses became failures that contrasted my success in the upper-level courses. I returned to full-time work and the ongoing conflict between its opportunities and its restrictions.

As a designer, I have been able to indulge my interests in typography, tactility, and sequences of reading. As a technologist, I have been able to indulge my interests in logic, workflow, and systems that can accommodate new developments. Personal work has let me indulge my interests in art, writing, history, and politics. Usually, what I lack is the luxury of exploring how all these fit together: How do you shape the experience of a reader or user? How do different media enhance or distort the information they convey? How can the richness of information in structural markup be expressed in print? How much of an author can a knowledgeable designer prove to be?

I have come to think of design as a means of conceiving and building the vocabulary, syntax, and cadence of unique dialects needed to express complex ideas in comprehensible ways. Doing those things well relies on the ability to grasp those complex ideas in the first place. Given the opportunity to study in the [name removed to increase the suspense] program, with its emphasis on process, investigation, conceptual development, and learning that goes beyond design itself, I hope to develop a methodology for achieving and encouraging real understanding as a fundamental aspect of practice not a luxury to enjoy when time, money, or business objectives permit, but an inherent strength.

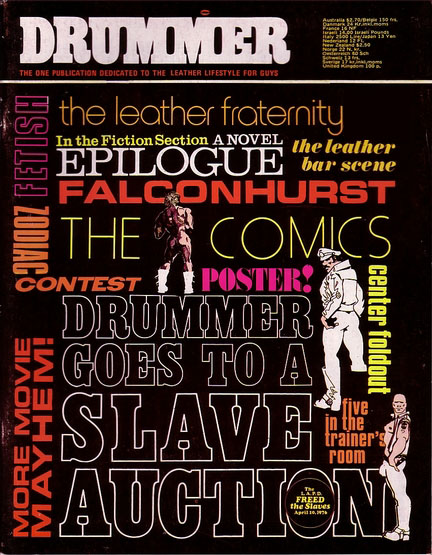

If you check out the January/February issue of (the not great but not completely terrible)

If you check out the January/February issue of (the not great but not completely terrible)  Here’s a brief excerpt:

Here’s a brief excerpt: