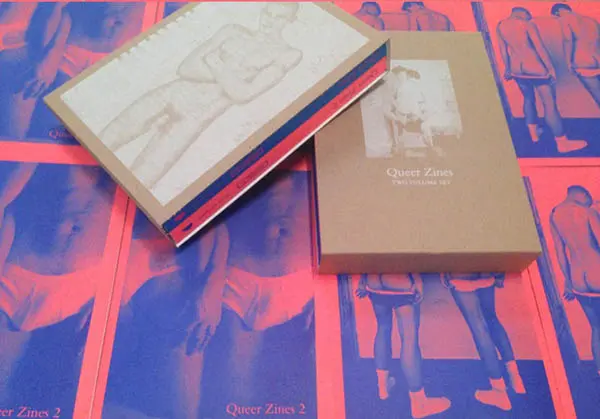

Queer Zines, reviewed on Brooklyn Rail

I didn’t know ahead of time that Pink Mince was going to be featured in this glorious publication, but I was awfully flattered to appear there.

Ragtag grab-bag

Queer Zines, reviewed on Brooklyn Rail

I didn’t know ahead of time that Pink Mince was going to be featured in this glorious publication, but I was awfully flattered to appear there.

The first of the longer reads form Pink Mince #3:

Ryskamp, by James Bainbridge

‘Much is made,’ he would say, ‘much is made of the innate homosexual narrative in Jekyll and Hyde. Much emphasis,’ he would say, ‘is given to it being what Showalter terms a reaction of the fin-de-siècle’s homosexual panic.’

In his office on the eighth floor (the lift only went as far as six) he would perch on the corner of his desk and say all of this without once looking up at you. He would sit there — one leg raised, the other touching the ground to stop himself toppling over — and direct this monologue response straight to the Satsuma he was in the process of unpeeling in his pale, bony hands.

‘Too much is given to that way of thinking of course. It’s a fashionable response. It’s very modish to approach everything with your queer-theory mask on right now. It gets funding. Produce a doctorate on the repetitive designation of Sapphic fisting in Charlotte Brontë, and you’re set for life.”

Only then would he look at you. He would look at you, and he would hold your gaze, and only then would he laugh.

‘Which is not to say,’ he would say, ‘which is not to say that all of this is not true about the story. Certainly all that’s there — look at that!’ he would exclaim, holding the skin of the satsuma from his forefinger and thumb, ‘got it off in one go!’

He would drop the skin into the metal wastepaper basket at his feet, turn the fruit over a few times in his hands and then, as if suddenly disinterested in it, put it down on the desk beside him.

‘Yes, all of that’s there. At the start of the story, before the truth of Jekyll’s transformation has been revealed, Utterson, the lawyer — the boring bloody lawyer — assumes that this figure Hyde must be blackmailing Dr Jekyll. He is taken care of in Jekyll’s will; he comes and goes at Jekyll’s house by his own leave. Utterson’s assumption is that there must be something improper about Jekyll’s relationship with Hyde; that Hyde is making him pay for some mis-demeanour in his youth. This intimation of blackmail, and Utterson’s -pronounced relief when this turns out not to be the case — the implication of all that I’d say is that Utterson is worried that Jekyll has been fucking Hyde.’

He would often swear like this, and it was clear that it was something he was not used to. He swore with the liberality of a man who evidently still found the word “fucking” quite shocking, and so would speak it to emphasise the contention of his point and then recoil from his lips as if afraid he had gone too far. It was an endearing quality in the man, this strange anachronistic politeness. It went hand-in-hand with his other mannerisms; his reluctance to make eye contact, his constant stoop as if embarrassed by his own physical form, his tendency to refer to himself in the third-person:

‘So, they’ve sent you to see Ryskamp, have they?’

And you would tell him that someone in the department had said that they thought the subject of your dissertation touched upon the area of his research. The truth was, nobody really knew what Dr Ryskamp did at all. His office was a clutter of books and framed prints, none of which appeared to bear any relationship with one another. His desk was hidden beneath a large map of South America, which he seemed to use mostly for scrawling down email addresses and phone numbers.

Ryskamp was a man much younger than people expected him to be. His exact age was indeterminately somewhere in his early thirties, though his outlook and mannerisms seemed to match a man possibly twice that. He once told you how he was interested in the vagueness of the physical description Hyde was given in the story:

‘All we really know is that he is shorter than Jekyll, but his face is left an intentional blank that cannot really be summed up by anyone.’

The same vagueness, you had thought, seemed to apply to Ryskamp. He was a meek, grey question mark who if you had not been sent to see, would have passed by unnoticed in a crowd. He was the last member of the department left on the eighth floor, and it seemed quite probable that the rest of the world had mostly forgotten his existence. As his room was unreachable by the lifts, he got by on the minimum of teaching.

‘What’s really interesting about the story however,’ he said to you, ‘is something far bigger than sexuality. Sexuality comprises it, certainly, but it’s a mistake to approach anything with a preconceived idea of what it’s about. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde suffers from this more than most, because it has passed so far into our cultural consciousness as an idea that few of us have stopped to actually read what it’s really saying.’

He walked over to the bookcase by the door, and after a period of searching he took down a slim grey volume and began to read.

‘This comes at the start of Jekyll’s written confession,’ Ryskamp said, ‘towards the end of the story. Before he conducted his experiment, Jekyll talks of how his life already felt divided between his “impatient gaiety of disposition” and his “imperious desire to carry his head high”. Obviously that separation in his character could translate to a man leading a publicly heterosexual life and a privately homosexual one, but that’s not really the key issue. He writes, “Many a man would have even blazoned such irregularities as I was guilty of; but from the high views I had set before me, I regarded and hid them with an almost morbid sense of shame. It was thus rather the exacting nature of my aspirations than any particular degradation of my faults, that made me what I was, and, with a deeper trench than in the majority of men, severed in me those provinces of good and ill which divide and compound man’s dual nature.”’

He put the book down on the desk and took from the fruit bowl another Satsuma, which he again began to skin.

‘It’s all there, you see. A simple reading is that Jekyll is divided between goodness and ill, and he suppresses this “wicked” side of himself for appearances sake — much as Utterson is seen to exist by cultural asceticism — but there’s so much more to it than that. The fundamental idea is that we exist in a dual nature; in part this is the separation of shame and guilt that we all essentially feel. Each of us has an interior life that is quite different from our exterior one; the private self that we do not necessarily wish others to publicly see. Yet the deep trench that Jekyll identifies runs deeper than that; it runs right through the private self also. “Man is not truly one,” Jekyll writes, “but truly two.” ’

He looked up from the fruit, and nodded as if he felt you understood.

‘It’s like Hegel’s master and slave dialectic. To truly know what we are, we have to first understand that other self, the thing within us that we outwardly decide we are not. There are things within you,’ he said concentrating on the Satsuma, ‘that exist — thoughts, feelings, emotions — that you identify, have experienced, but do not claim as part of your own identity. Dark thoughts, perhaps,’ he said and he stared at you hard.

‘There’s nothing wrong in that. Thoughts don’t define our character. We can’t select those things that we dream about. Leigh Hunt tried, of course, kept his son from any exposure to distress or supernatural themes. Charles Lamb wrote of the boy that no child he had ever known had suffered worse night terrors. They were all his brain’s invention. The point is, we all have that Other within us, and despite our external appearances we know that it is there, always lurking in our shadow.

‘Yet stubbornly we cling to this view of ourselves as singular; as individuals. We deny this Other self because we take it to be somehow unnatural, associating it, in our almost superstitious approach to mental health, to be dangerously close to the realm of the schizophrene. Yet it’s a relatively modern assumption that contained within this skin is only one identity; only under the Fifth Lateran Council in the sixteenth century does the notion of an unpartitioned soul, really take hold. Before that we were happy to believe that within us existed multiple forms — and that’s just in Europe — ’

He leapt from the desk and dragged off the oversized map of South America to reveal a series of yellowed lithographs depicting tribal dancers.

‘Aztecs,’ he exclaimed, ‘at the same time that we were deciding we were of one distinct mind, in South America people were putting on costumes to occupy those other parts of themselves; dividing themselves up in sacrifice to release the forces held within them to the Gods.’

‘See this,’ he said pushing a print of a man towards you, ‘at Tlacaxipehualiztli they would flay men and dress in their skins, and in so doing would occupy a part of themselves other to their day to day existence. It is the same as Jekyll; the potion does not make him a monster, it merely changes his appearance, devolves his highborn looks. Putting on a different skin — ’ he said, ‘it’s only by putting on a different skin that you’re able to know that Other self, and ever know what you really are.’

— — —

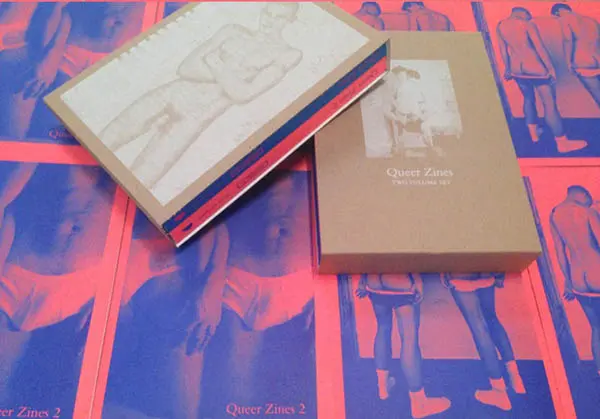

You saw him a few more times over the course of that term. He further expanded on this thinking; on how Jekyll’s transformation went against the tide of evolution. He showed you various engravings of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and photographs of Nigerian tribesmen dressed in gas masks as effigies to Gods. He told you how he felt devolution was the only route for the modern brain; that our prized fetishism of individuality led each of us to view ourselves as Gods, and there was no way forward from that; that he saw Jekyll’s public face just as constructed and monstrous as the debased one of Hyde.

On your return after the summer, Ryskamp was gone, and being the only person known to have spent any time with him in the last few years, you found yourself enlisted to help clear his office.

A thick grey pelt had grown across the Satsumas left in the bowl, and their undressed skins dissolved into a snowy dust of spores inside the bin. You rolled up the map of South America, and helped the building manager empty the shelves of books into boxes to be taken away.

Nobody seemed to know where Ryskamp had gone to, only that he was not coming back. You took down the postcards from their blu-tack mounts left upon the window ledge, and you picked out your favourite prints from his collection and you kept them for yourself.

Finally, the room now bare and to be used for the storage of photocopier paper and student records, you cleared his computer of the photographs you took to be Ryskamp’s fate.

‘The unlikeliness,’ he would have said, ‘the unlikeliness of this respectable figure, a doctor for heaven’s sake, a responsible high-minded individual living his final days as a degenerate, as a faceless monster – is not unlikely at all. The external skin is balanced against the internal instinct. It’s within all of us.’

For here were the photographs of Ryskamp in his Other’s skin; reduced to the primitive functions of an organism. You stripped them from the hard drive and shut the computer down one final time. At least you took it to be Ryskamp. Beneath the black, glossy skin and metallic-banded eyes, it could have been anyone.

Originally published in the late Fall of 2009, Pink Mince #3 — Alter Egos & Secret Identities — is now out of print. You can still get other issues of the zine at pinkmince.com

Christopher Street Magazine. September 1979. Page 9.

William Friedkin’s Cruising (1980) was not warmly received by gay activists. He was already on their shitlist due to directing The Boys in the Band (1970), and they weren’t about to let him repeat the offense sitting down. The issue with both films was what Friedkin, as a metonym for the film industry in general, chose to prioritize in his representation of gays. With The Boys in the Band, it was the high-pathos, distinctly unliberated attitudes of its principal characters, and with Cruising, it was serial murders and leather bars.

Vito Russo’s Celluloid Closet gets at why people would object to the movie even during its filming. First there’s the source material:

The novel, while exploiting the socially instilled self-hatred of an unstable character, is homophobic in spirit and in fact; it sees all its gay characters as having been “recruited,” condemned to the sad gay life like modern vampires who must create new victims in order to survive.

Then there are the circumstances of filming:

Yet he used the Greenwich Village ghetto and scores of gay extras… to make a film about a series of grisly murders patterned not on Walker’s book but on the killings of gay men that had been reported widely in the press in the late 1970s. Friedkin’s screenplay incorporated the locales and the modus operandi of several real-life Greenwich Village murders, and Friedkin consulted in prison with Paul Bateson, who was convicted of killing Variety critic Addison Verrill and had once had a bit part as a medic in Friedkin’s film The Exorcist.

These ripped-from-the-headlines details and real world settings then lend false verisimilitude to a bullshit story that imagines the gay demimonde as inherently violent. Or at least it would, if the movie were coherent enough to get its bad ideas across. The mini-documentaries that come with the film show that these ideas did inform the making of the film. In a featurette titled “Exorcising Cruising,” the actor who played one of the murderers, Richard Cox, says, “I think one of the things that Billy [William Friedkin] was saying is that there’s this X factor out there. That there’s a violent killer always lurking. It goes on. There’ll always be another.”

This and the indeterminate identity of the killer(s) is played up in the featurette as a spooky commentary on the human condition or a horror movie device to get you jumping at shadows when you’re back at home. It might have been, if the killers and victims had come from all segments of society. Instead, it targeted just one that happened to routinely be imagined as tragic, evil or both in the sparse representation it actually ever got.

Both films have since been reappraised and rehabilitated, but neither film was quickly or completely forgiven. In the May 25th, 1992 issue of Christopher Street, critic Bob Satuloff said that Cruising “has got to be the most homophobic movie ever made.”

But would you believe I had a mostly positive impression of the movie before writing it up? It’s only the source material, social context at the time of release, and stated intentions of the creators that are damning! You know, only those little things. The leather bar scenes are absolute catnip to me and likely most people reading this. The scene where Pacino, an undercover cop, visits a bar filled with writhing, eroticized simulacra of his co-workers is one of the most amazing moments in any gay-themed movie I’ve seen. The killer’s “You made me do that” catchphrase sounds in 2014 hilariously close to Urkel’s “Did I do that?” It now fits Susan Sontag’s formulation of camp: passionate, failed seriousness, rendered lovable by distance in time.

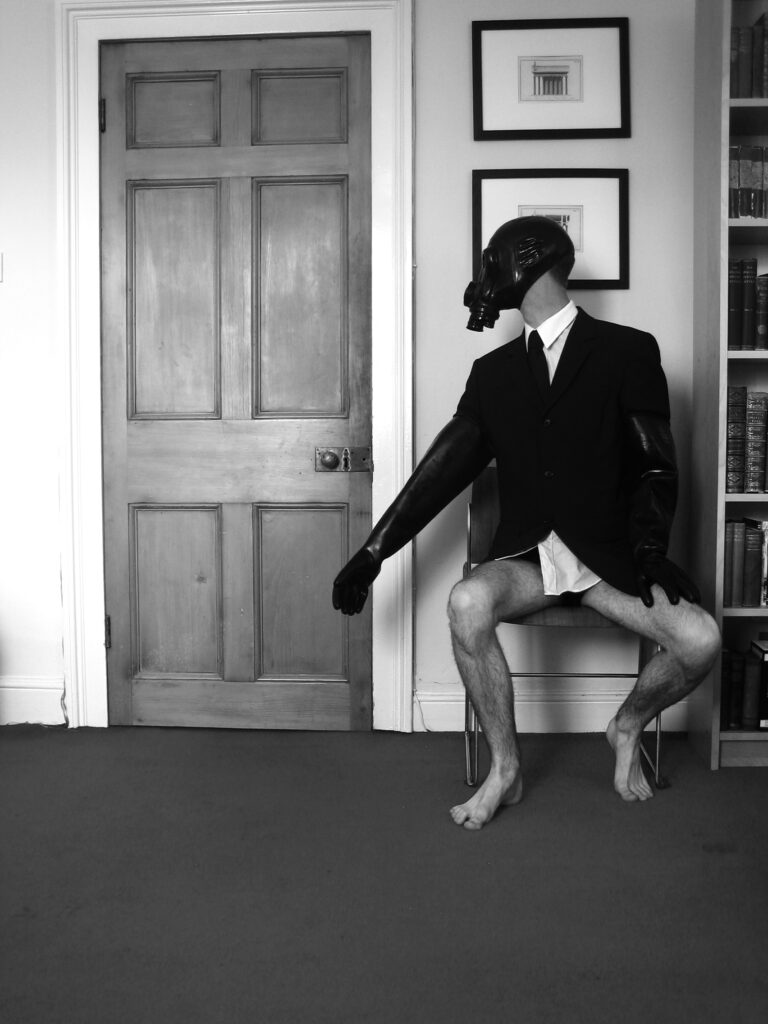

Title: Knight

Author: Impleat Forum

Publisher: Flushing, NY: Impleat Forum

Subject:

Note: Personals for bondage, spanking, leather, and discipline

Yet another project I’ve been meaning to write more about at length, but haven’t had the time to do so properly. However, here’s a video in which I say most of what I’ve been meaning to write:

Dan Rhatigan on Ryman Eco from Grey London on Vimeo.

Ryman Eco from Grey London on Vimeo.

That’s me, being a nerd talking about my nerdy tattoos. By the way, may I once again recommend taking a look at Pink Mince #10 — Ink Mince?

Catholics have more extreme sex lives because they’re taught that pleasure is bad for you. Who thinks it’s normal to kneel down to a naked man who’s nailed to a cross? It’s like a bad leather bar.

[From The Advocate, June 28, 2014]

Polaroids From The Golden Age of the Orgy: 1978

In the Advocate: “Full moon” parties were regularly held, as were events planned around a theme. Patrons were encouraged to bring costumes — from feathered masks to black leather uniforms — and a bowl of psychedelic punch was often set out. For a while there were life drawing classes, Tantric massage classes, and a weekly drop-in support group lead by a hip shrink. Members of these groups were encouraged by the offer of a free locker to spend the evening and this helped foster a more familiar and intimate atmosphere than was common in other gay bathhouses of the era. The sense of playfulness and camaraderie there was palpable. No more so than the night when the city’s reigning disco diva, Sylvester himself, came to party down.

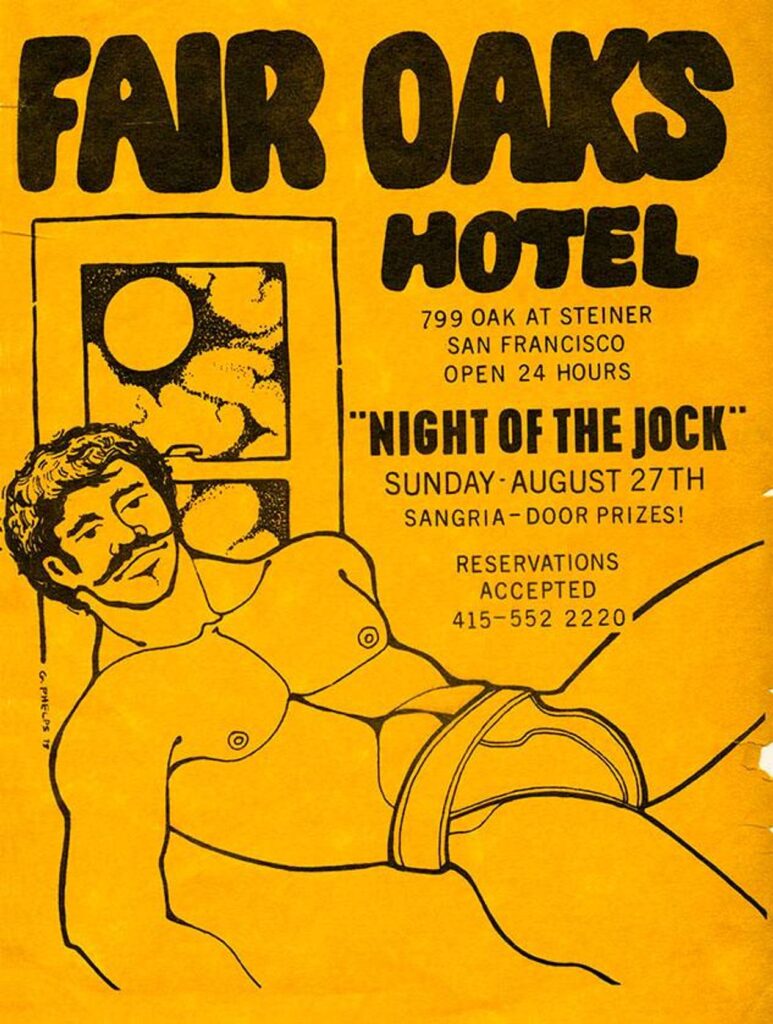

Dug into the bedrock beneath the Fairoaks (below the sauna, glory holes, and sling), was the basement office and living quarters for some of the owners and staff. There were eight partners, including Melleno and his lover, Rob Mullis. Many of those men, like a great number of Fairoaks patrons, are no longer alive — taken by the plague of AIDS that would decimate the city’s gay population in just another few years.

Like a string of black pearls, San Francisco’s bathhouses adorned the city with a touch of louche glamour before they were officially closed in October 1984. The Houthouse, the Barracks, the Handball Express, Animals, the Club, Bulldog, Sutro, and, down by the tracks, the Ritch Street Baths. The ever-notorious South-of-the-Slot, and so many more. Each claimed a distinct character and clientele. But no place had quite the feeling of coming home once through the front door as did the Fairoaks.”