The first of the longer reads form Pink Mince #3:

Ryskamp, by James Bainbridge

‘Much is made,’ he would say, ‘much is made of the innate homosexual narrative in Jekyll and Hyde. Much emphasis,’ he would say, ‘is given to it being what Showalter terms a reaction of the fin-de-siècle’s homosexual panic.’

In his office on the eighth floor (the lift only went as far as six) he would perch on the corner of his desk and say all of this without once looking up at you. He would sit there — one leg raised, the other touching the ground to stop himself toppling over — and direct this monologue response straight to the Satsuma he was in the process of unpeeling in his pale, bony hands.

‘Too much is given to that way of thinking of course. It’s a fashionable response. It’s very modish to approach everything with your queer-theory mask on right now. It gets funding. Produce a doctorate on the repetitive designation of Sapphic fisting in Charlotte Brontë, and you’re set for life.”

Only then would he look at you. He would look at you, and he would hold your gaze, and only then would he laugh.

‘Which is not to say,’ he would say, ‘which is not to say that all of this is not true about the story. Certainly all that’s there — look at that!’ he would exclaim, holding the skin of the satsuma from his forefinger and thumb, ‘got it off in one go!’

He would drop the skin into the metal wastepaper basket at his feet, turn the fruit over a few times in his hands and then, as if suddenly disinterested in it, put it down on the desk beside him.

‘Yes, all of that’s there. At the start of the story, before the truth of Jekyll’s transformation has been revealed, Utterson, the lawyer — the boring bloody lawyer — assumes that this figure Hyde must be blackmailing Dr Jekyll. He is taken care of in Jekyll’s will; he comes and goes at Jekyll’s house by his own leave. Utterson’s assumption is that there must be something improper about Jekyll’s relationship with Hyde; that Hyde is making him pay for some mis-demeanour in his youth. This intimation of blackmail, and Utterson’s -pronounced relief when this turns out not to be the case — the implication of all that I’d say is that Utterson is worried that Jekyll has been fucking Hyde.’

He would often swear like this, and it was clear that it was something he was not used to. He swore with the liberality of a man who evidently still found the word “fucking” quite shocking, and so would speak it to emphasise the contention of his point and then recoil from his lips as if afraid he had gone too far. It was an endearing quality in the man, this strange anachronistic politeness. It went hand-in-hand with his other mannerisms; his reluctance to make eye contact, his constant stoop as if embarrassed by his own physical form, his tendency to refer to himself in the third-person:

‘So, they’ve sent you to see Ryskamp, have they?’

And you would tell him that someone in the department had said that they thought the subject of your dissertation touched upon the area of his research. The truth was, nobody really knew what Dr Ryskamp did at all. His office was a clutter of books and framed prints, none of which appeared to bear any relationship with one another. His desk was hidden beneath a large map of South America, which he seemed to use mostly for scrawling down email addresses and phone numbers.

Ryskamp was a man much younger than people expected him to be. His exact age was indeterminately somewhere in his early thirties, though his outlook and mannerisms seemed to match a man possibly twice that. He once told you how he was interested in the vagueness of the physical description Hyde was given in the story:

‘All we really know is that he is shorter than Jekyll, but his face is left an intentional blank that cannot really be summed up by anyone.’

The same vagueness, you had thought, seemed to apply to Ryskamp. He was a meek, grey question mark who if you had not been sent to see, would have passed by unnoticed in a crowd. He was the last member of the department left on the eighth floor, and it seemed quite probable that the rest of the world had mostly forgotten his existence. As his room was unreachable by the lifts, he got by on the minimum of teaching.

‘What’s really interesting about the story however,’ he said to you, ‘is something far bigger than sexuality. Sexuality comprises it, certainly, but it’s a mistake to approach anything with a preconceived idea of what it’s about. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde suffers from this more than most, because it has passed so far into our cultural consciousness as an idea that few of us have stopped to actually read what it’s really saying.’

He walked over to the bookcase by the door, and after a period of searching he took down a slim grey volume and began to read.

‘This comes at the start of Jekyll’s written confession,’ Ryskamp said, ‘towards the end of the story. Before he conducted his experiment, Jekyll talks of how his life already felt divided between his “impatient gaiety of disposition” and his “imperious desire to carry his head high”. Obviously that separation in his character could translate to a man leading a publicly heterosexual life and a privately homosexual one, but that’s not really the key issue. He writes, “Many a man would have even blazoned such irregularities as I was guilty of; but from the high views I had set before me, I regarded and hid them with an almost morbid sense of shame. It was thus rather the exacting nature of my aspirations than any particular degradation of my faults, that made me what I was, and, with a deeper trench than in the majority of men, severed in me those provinces of good and ill which divide and compound man’s dual nature.”’

He put the book down on the desk and took from the fruit bowl another Satsuma, which he again began to skin.

‘It’s all there, you see. A simple reading is that Jekyll is divided between goodness and ill, and he suppresses this “wicked” side of himself for appearances sake — much as Utterson is seen to exist by cultural asceticism — but there’s so much more to it than that. The fundamental idea is that we exist in a dual nature; in part this is the separation of shame and guilt that we all essentially feel. Each of us has an interior life that is quite different from our exterior one; the private self that we do not necessarily wish others to publicly see. Yet the deep trench that Jekyll identifies runs deeper than that; it runs right through the private self also. “Man is not truly one,” Jekyll writes, “but truly two.” ’

He looked up from the fruit, and nodded as if he felt you understood.

‘It’s like Hegel’s master and slave dialectic. To truly know what we are, we have to first understand that other self, the thing within us that we outwardly decide we are not. There are things within you,’ he said concentrating on the Satsuma, ‘that exist — thoughts, feelings, emotions — that you identify, have experienced, but do not claim as part of your own identity. Dark thoughts, perhaps,’ he said and he stared at you hard.

‘There’s nothing wrong in that. Thoughts don’t define our character. We can’t select those things that we dream about. Leigh Hunt tried, of course, kept his son from any exposure to distress or supernatural themes. Charles Lamb wrote of the boy that no child he had ever known had suffered worse night terrors. They were all his brain’s invention. The point is, we all have that Other within us, and despite our external appearances we know that it is there, always lurking in our shadow.

‘Yet stubbornly we cling to this view of ourselves as singular; as individuals. We deny this Other self because we take it to be somehow unnatural, associating it, in our almost superstitious approach to mental health, to be dangerously close to the realm of the schizophrene. Yet it’s a relatively modern assumption that contained within this skin is only one identity; only under the Fifth Lateran Council in the sixteenth century does the notion of an unpartitioned soul, really take hold. Before that we were happy to believe that within us existed multiple forms — and that’s just in Europe — ’

He leapt from the desk and dragged off the oversized map of South America to reveal a series of yellowed lithographs depicting tribal dancers.

‘Aztecs,’ he exclaimed, ‘at the same time that we were deciding we were of one distinct mind, in South America people were putting on costumes to occupy those other parts of themselves; dividing themselves up in sacrifice to release the forces held within them to the Gods.’

‘See this,’ he said pushing a print of a man towards you, ‘at Tlacaxipehualiztli they would flay men and dress in their skins, and in so doing would occupy a part of themselves other to their day to day existence. It is the same as Jekyll; the potion does not make him a monster, it merely changes his appearance, devolves his highborn looks. Putting on a different skin — ’ he said, ‘it’s only by putting on a different skin that you’re able to know that Other self, and ever know what you really are.’

— — —

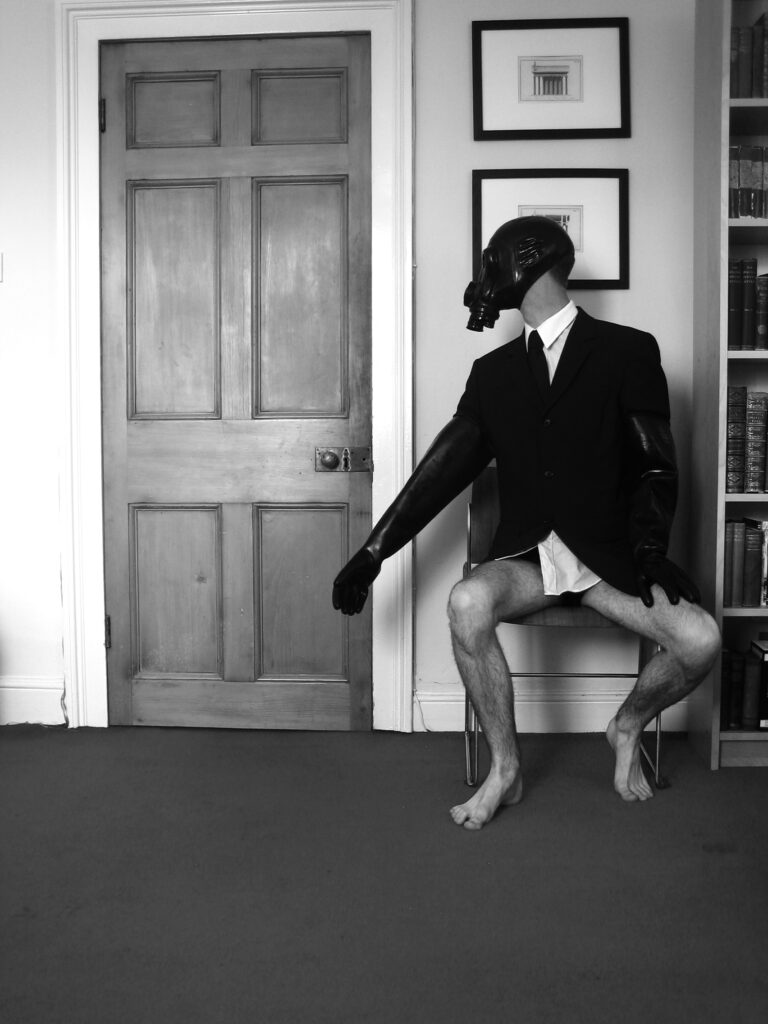

You saw him a few more times over the course of that term. He further expanded on this thinking; on how Jekyll’s transformation went against the tide of evolution. He showed you various engravings of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and photographs of Nigerian tribesmen dressed in gas masks as effigies to Gods. He told you how he felt devolution was the only route for the modern brain; that our prized fetishism of individuality led each of us to view ourselves as Gods, and there was no way forward from that; that he saw Jekyll’s public face just as constructed and monstrous as the debased one of Hyde.

On your return after the summer, Ryskamp was gone, and being the only person known to have spent any time with him in the last few years, you found yourself enlisted to help clear his office.

A thick grey pelt had grown across the Satsumas left in the bowl, and their undressed skins dissolved into a snowy dust of spores inside the bin. You rolled up the map of South America, and helped the building manager empty the shelves of books into boxes to be taken away.

Nobody seemed to know where Ryskamp had gone to, only that he was not coming back. You took down the postcards from their blu-tack mounts left upon the window ledge, and you picked out your favourite prints from his collection and you kept them for yourself.

Finally, the room now bare and to be used for the storage of photocopier paper and student records, you cleared his computer of the photographs you took to be Ryskamp’s fate.

‘The unlikeliness,’ he would have said, ‘the unlikeliness of this respectable figure, a doctor for heaven’s sake, a responsible high-minded individual living his final days as a degenerate, as a faceless monster – is not unlikely at all. The external skin is balanced against the internal instinct. It’s within all of us.’

For here were the photographs of Ryskamp in his Other’s skin; reduced to the primitive functions of an organism. You stripped them from the hard drive and shut the computer down one final time. At least you took it to be Ryskamp. Beneath the black, glossy skin and metallic-banded eyes, it could have been anyone.

Originally published in the late Fall of 2009, Pink Mince #3 — Alter Egos & Secret Identities — is now out of print. You can still get other issues of the zine at pinkmince.com