During the second half of the twentieth century, the United States moved toward greater social acceptance of LGBT people, due to the cumulative efforts of numerous groups engaged in social and political activism. One of the many challenges facing any attempt to bring together a community of gay people was the difficulty of producing and distributing any books or periodicals with overtly gay content, which was under threat of various methods of censorship. However, even as legal hurdles fell away, social censure remained an ongoing challenge to gay communities and the publications targeted to them.

During that same period, the graphic arts industry experienced its own rapid evolution, as the development of ever faster and cheaper means of typesetting and printing made a greater variety of typographic choices available with fewer barriers to their use and reproduction. Typewriters, phototypesetting systems, rub-down type, and eventually desktop publishing software provided an increasing number of ways to easily prepare text for layout and reproduction, with less and less formal training required to do so.

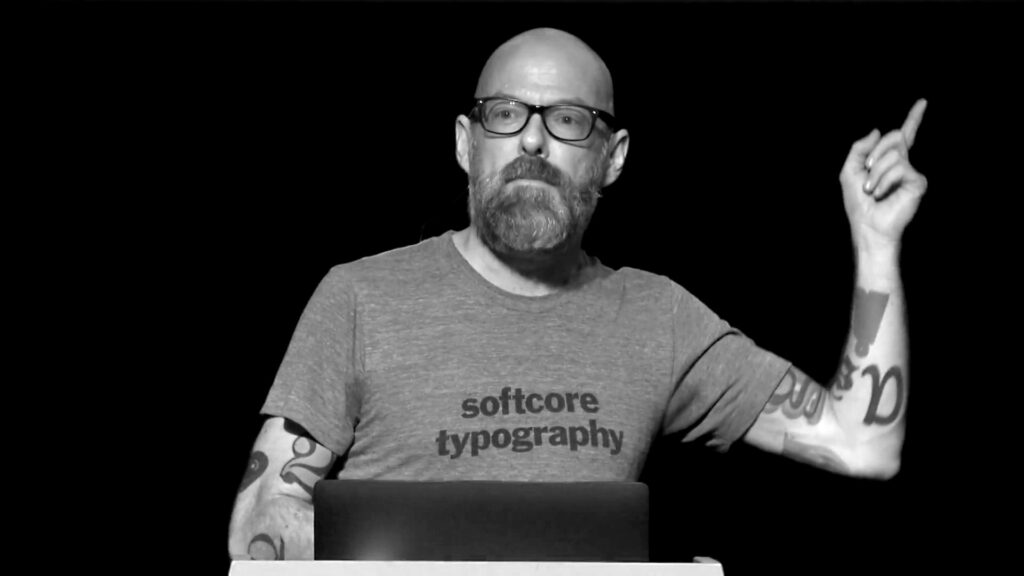

Suffice to say, there was both the will and the ways to publish to gay audiences, whether the message was intended to lift up or turn on. A comprehensive discussion of that complex intersection of social and graphic history would be a meaty text. For now, this is a look at how I started to find some refreshing original design in a space where publishers and designers weren’t concerned with what the mainstream thought of them. When I stripped away the pornography from the pornography, I discovered how much lively typography had been hiding in plain sight.

This journey started when I stumbled across a beautiful and an unexpected old magazine cover, and that led to a little project, which then led to research and many more questions. The magazine in question was the beefcake-focused premiere issue of Bold (1978), but what really caught my eye was its use of the typeface Stilla by François Boltana. I have always struggled to find examples of Stilla in use, no doubt because its zesty letterforms can be awfully difficult to compose. The letters have to be arranged with care, and it almost never sets all that easily by default. I tried to recreate the title setting for a small project and realized that this particularly helpful form of L didn’t exist in the digital typeface. The answer was in my reference material — a Letraset specimen book. The original version published by Letraset in 1973 included a number of alternate characters for many letters, including that form of the L that I was looking for. It made sense in1978 to use Letraset for the titling graphics, and it certainly made sense for a typeface like Stilla that works at its best when set down one letter at a time, consciously controlling the combination of the forms. This small epiphany led me to look more closely at how other magazines of the era handled their typefaces.

Later, I encountered an image of the cover from Drummer magazine (issue no. 6, May/June 1976), a title better known for its hardcore S&M content than its exquisite typography. Drummer was a very adult magazine specializing in very adult themes, but in this case it avoided photography in lieu of a typographic cover design that is really well-composed, and essentially a Letraset specimen poster. It was surprising once again to see a magazinelike this taking such a fresh approach in its design.

These initial surprises felt more significant as I thought about about the means of production available to these publications. I identified some Letraset typefaces that I liked, and I was surprised at how they were used. My curiosity was further piqued, and I started gathering up reference material: not for the pictures or the articles, but for the expressive typography. I found more magazines with surprising type choices and sensitive type compositions, and assumed that these were not under the same kind of commercial pressures to be as tasteful as the mainstream titles found on newsstands.

There is an instinct to react to the campy humor of dirty magazines with the funny titles. A magazine called Hot Dog! (Hold the Buns) from the mid-1980s isn’t shying away from puns, but the title inspires an extra smile if you know that the typeface used is Letraset Frankfurter. In-jokes aside, this is set pretty well. The composition is not the freshest but it responds to the main focus of the photograph. Considering how a magazine before the age of desktop publishing had to be producedby assembling analog materials, it is not amateur work. To be able to practice everyday graphic production in this era required a number of refined visual and manual skills. Letraset’s Spacematic system — the carefully positioned hash marks along the baseline of each line on a sheet of lettering — provided some help with rub-down type, but you still needed to be able to space type relatively well, and be able to make optical adjustments when aligning letters or words. You had to know how to apply type carefully and firmly onto a layout board, how to scale artwork using a stat camera, and how to prepare layered mechanical paste-ups for color separation and printing.

The work seen in these magazines may not reflect the height of graphic design, but it was still work that required some degree of training and familiarity with graphic art materials and production for print. If you wanted to publish a magazine, you had to rely on someone who had a basic understanding of the methods of production and probably some understanding of design or some opinions about design and typography.

I am pretty sure this explains a lot of the choices I discovered. You have the combination of a product like Letraset which is very accessible and inexpensive compared to commercial typesetting services, so it was an easy way to provide variety in a crowded market segment in which titles needed to distinguish themselves from one another with minimal investment, since the cover photography was the primary selling point. I don’t think there were lot of staff meetings about the cover typography for these magazines. I think people were given a stack of photos and told to “slap together a cover so this can go to the printer” and those people with a bit of training and a lot of latitude took the opportunity to have what fun they could.

There are many, many examples of this, particularly during the 70s and the early 80s — before the age of digital typography, in the era when retail lettering products like Letraset, Chartpak, Zip-a-Tone, Mecanorma, et al. were challenging the dominance of phototypesetting. The accessibility of rub-down type is a catalyst for much of what we see in the publications from this era.

Despite use of Letraset Rodeo, Studs in Leather (issue no. 1, 1976) has nothing to do with the wild west. (Rodeo has been adapted by many people, but the version used here matches pretty well to the Letraset version.) Once again the typefaces used on the cover have all come from Letraset’s collection. The condensed sans serif is Letraset Compacta by Fred Lambert, the most successful of their original typefaces. The date and price are set in 12 pt. Helvetica Bold caps, the most frequently recurring detail of all the covers I’ve studied.

Despite the prominence of rub-down type in many cover layouts, phototypesetting was still the primary method of setting headlines and text type until PostScript fonts and desktop publishing software supplanted it in the late 1980s. When photoset type appears in cover layouts, It often lacks the sharpness that you see in rub-down type. It tends to be a little bit soft from phototype’s inherent optical degradation, a by-product of multiple stages of photographic scaling and reproduction. (Rub-down type suffered much less in its manufacturing process, although if the artwork was scaled with a stat camera after application, it tended to soften around the edges just as much as phototype.) While the sharpness of phototype could vary, it can be clearly identified by its consistent alignment and methodical spacing, ensured by a typesetting system. It was often the better solution for setting longer lines or short passages of text that might appear on a cover, and certainly the best solution for body copy.

What is consistent in the blocks that I have been able to identify as phototypesetting, however, is that while the spacing of text is consistent, it is often poor. The designers did not seem to pay for the highest quality composing services. But would professional type shops have taken on obscene jobs like these? A factor in the use of Letraset and other kinds of rub-down type for these magazines was likely that it bypassed the middleman: one less service bureau that may not want to handle gay porn.

(After speaking about this subject at the 2017 ATypI conference in Montreal, Alan Wahler, who worked as a typesetter in New York during the 1970s and 1980s, told me that customers would regularly sneak headlines and captions for adult material within the middle of more mundane jobs. The typesetters would encounter specs for random bits of copy that didn’t quite make sense, but the overall context was obscured.)

Letraset was invented to be a professional graphic arts tool. The company rapidly discovered that it made typography very accessible in ways that were more significant than they anticipated. It democratized typesetting by making it possible for someone to go into an art or design supply store and buy their type easily and inexpensively. When you are able to buy a sheet of rub-down type and throw a layout together It was more likely for people without training, people without a design or graphic arts background to try their hand at a bit of publishing and set a little text. That was very powerful. You can see an explosion of graphic ephemera from the late 20th century because of that accessibility, that chance for someone without a graphic arts background, someone who may have neither the training or other resources, to make something on their own with well-crafted typefaces.

Letraset and other brands of rub-down type rose to the forefront of the marketplace during the ’60s, a time of incredible of social upheaval in the west. Just as there was an explosion of underground press supporting civil rights, women’s liberation, and anti-war sentiments, there was also the dawn of a gay press. For gay publishers and readers, barriers were falling down that made it possible for the first time to produce and distribute material with overtly homosexual content. Social acceptance is a slow process, however: it was still very handy for publishers of gay material to have access to democratized means of production.

The earliest gay publications in the United States struggled against adversity both legal and practical because of the nature of their content. Digest-sized, single-color magazines such as One (launched in January 1953) and Mattachine Review (launched in January 1955) featured news, politics, and literary articles rather than anything sexual in nature, yet were harassed by law enforcement and the U.S. Postal Service alike. The Postal Service refused to mail One on grounds of obscenity, a decision which was eventually overturned by the Supreme Court in 1957. Mattachine Review tread more carefully with the authorities, but the reluctance of printers to take on a job that might be subject to prosecution led the Review’s publisher to set up his own typesetting, design, and printing service, the Pan-Graphic Press.

Similarly, Herbert Lynn Womack started his own printing business in order to publish a series of magazines under the imprint of MANual Enterprises (later known as the Guild Press). MANual Enterprises titles featured overtly homoerotic collections of photography without explicitly declaring homosexual intent, However, this was enough to raise suspicion. Parcels containing three of Womack’s titles — Grecian Guild Pictorial, MANual, and Trim — were seized by the Postal Service in 1960, which eventually led to a 1962 Supreme Court decision that ruled that nude or near-nude models did not necessarily qualify as obscenity.

These first few court rulings paved the way for a small explosion in modestly produced publications for a gay market, a customer base that sought out these titles furtively in the years before the the legal triumphs and Stonewall and increasing social acceptance. This was the era of the physique magazine, such as those published by Womack and MANual Enterprises. Physique magazines kept a very straight face, as it were, in talking about the subject matter. They promoted themselves as champions of physical culture, exercise, improving your muscle tone, watching your weight through healthy diet, and posing for the edification of artists and photographers who needed models to help them practice their own craft. This was a conscious attempt to co-opt the aesthetics of typical magazines about sport, shifting the visual and editorial direction just enough to resonate with a gay audience.

As Womack’s efforts were emboldened by his victory in the Supreme Court and his control of his own press, the photographs in MANual spoke less to classical ideas of form, and started to become more suggestive and prurient. As the veil of pure athleticism was dropped, many physique magazines also reduced the amount of cover copy devoted to articles on health and sport, and relied more on attention-grabbing mastheads and bold photography. While Letraset and its plethora of display typography hadn’t fully saturated the publishing market yet, the change in tone was happening that was ready to embrace it.

The increasing acceptance and visibility of gay publications encouraged the growth of numerous gay lifestyle magazines, which often mixed culture and politics with a dash of nudity. More newsstand-friendly, yet still wanting to reach gay readerships in urban areas, these titles often relied on typefaces popular in more mainstream media. Dilettante launched in 1974 with a lot of photography that might raise an eyebrow, but featured articles on books and plays and movies, all set with a trendy mix of Letraset’s version of A. M. Cassandre’s Peignot (already well-known thanks to Mary Tyler Moore), Herb Lubalin and Tom Carnese’s ITC Avant Garde, and trusty Helvetica. In 1975, Dilettante rebranded itself as Mandate, but kept the same typographic formula for many more years.

Drummer, launched in 1975, bridged a gap between the increasingly explicit descendants of the physique magazines, and the eclectic contents of the urbane lifestyle magazines, Drummer was a community magazine focused on gay male S&M communities, calling its readership the “Leather Fraternity”. It grew out of a political newspaper of the same name — the newsletter of the Homophile Effort for Legal Protection, based Los Angeles in the early 70s. H.E.L.P.’s Drummer newsletter already featured the incredible mix of type that made the magazine stand out later. Initially, this graphic effort helped to make the a newsletter about legal issues more appealing and friendlier to the community. When the newspaper folded, and Drummer relaunched itself as a magazine “dedicated to the leather lifestyle for guys”, it became more clear that the typography reflected the graphic sensibilities of publisher John Embry, whose apparent love of Letraset’s typefaces provided a visual thread that connected the newsletter and the first 100 issues of Drummer, despite a frequently changing roster of art directors and designers. When Drummer changed hands after its 100th issue and Embry moved on to publish other titles, his love of Compacta, Avant Garde, and Walter H. McKay’s Egyptienne went with him.

The unique characteristic eclecticism of Drummer’s typography certainly helped it stand out from both the stroke magazines of the day — flashy title treatments but little cover copy — as well as the mainstream gay lifestyle magazines — more verbose yet more typographically predictable. The playfulness of the covers provided a palatable contrast to the sexually graphic content within, and gave Drummer a clear identity that contributed to its success as it connected scattered S&M communities around the country.

Drummer’s look settled down in the years after Embry’s departure in 1986, which coincided with a steady shift toward desktop publishing software as a means of production. It was an uncomfortable evolution, as the typography became more formulaic and a little bit less sensitive to how things were handled. The overall composition of image and text became less considered, and playful choices from the Letraset library were replaced with formulaic use of the early digital versions of Helvetica and Futura, distorted and outlined and colored in ways made possible by the new software. As those means of production evolved, they showed changing nature of the skills needed to practice graphic design, and the inherent perceptual skills needed to work with Letraset and paste up strips of phototype gave way to the technical skills needed to assemble documents in PageMaker and Quark XPress.

All this increasingly less casual research led to an issue of Pink Mince, a little zine that I’ve been publishing for some years. I just wanted to look at the typography of all the magazines I had been gathering and reset the layouts from scratch, so I made sure that I had to up to date subscriptions to Typekit (now known as Adobe Fonts, and where I work) and Monotype Library Subscription (R.I.P.) in order to track down all the typefaces I needed. Luckily, most of the Letraset library that is available digitally passed on through ITC and on to Monotype so I could get most of the fonts. The typefaces that were digitised by URW were available from Typekit, so aside from a few outliers I had what I needed in some digital form. What I wasn’t expecting as I worked on the designs was that recreating the original typesetting, right down to the letter spacing, made it immediately obvious how all these covers were originally produced.

I redrew that L from Stilla, which didn’t take that much time. Luckily I had the Letraset specimens to use as a guide. More vexing was that none of that Helvetica used in the original covers is spaced the way you will find it in a font today. Everything had to be reviewed letter by letter to match the original spacing, and occasionally I even had to push the baseline up and down a couple of points or fraction of a point to match the original alignment. It wasn’t consistent enough to be phototypesetting in many cases, which was the clue that it was set by hand with Letraset or another brand of rub-down type. I could identify and replicate phototypeset lines since at least the spacing would be consistent, even when it was weird.

I love Frankfurter as a typeface, so I definitely had to do Hot Dog. The tight spacing of the Compacta Italic on its is very different letter by letter, like the tightness of the Frankfurter. This is not the rhythm that comes from the digital typefaces that are available.

You also start seeing when you look just that typography of these magazines that they go beyond the tasteful recommendation of “stick to two typeface families” and often effectively mix a lot of typefaces. In many cases it will be a detail like the price set in a different typeface, in order to use clearer numbers or a different size than other typefaces in the layout, or there may be a warning label that needs to jump out from the other elements on the page. Despite this riot of different typefaces, the overall effect can be relatively cohesive.

This frequent mixing is also innate to working with a material like Letraset, where a designer may have a pile of different sheets available, and would have to switch to a different typeface if only to set text at a different size, or because a sheet of a given design may have run out of the glyphs need. This practical eclecticism went away as these publications moved into the digital space, where it’s much easier to scale the text and there were no limits to the use of any characters found in a font. That’s when you see magazines following the more modernist approach of using just a couple of typeface (somewhat) tastefully throughout the cover.

Once desktop publisher became the working method of choice, the type choices were typically blander, and even the compositions are a lot more straightforward. Instead of careful arrangement of elements, there was more overlapping of type and graphic elements, which was a lot easier to do with software than it was for multilayered mechanicals and the analog reproduction methods.

There is a social history to the means of production for all things, even the tawdry genre of adult magazines. I can barely scratch the surface of this particular intersection of culture, civil rights, sexual expression, and opportunism. Even if the subject matter is not your personal cup of tea, investigating the publications and related ephemera of a specific community still gives some insight into an era of rapid change in the graphic arts, and how successfully technological advances democratised design and publishing, for highbrow and lowbrow subjects alike.

Read your entire essay. Very interesting. Well done. Goes nicely with all the writing I have done in and about Drummer over the last 42 years. As a matter of credit, at Drummer, because of our art director Al Shapiro, we paid a lot of attention to our “look.” We at the Drummer Archives thank you for your kind words about our esthetic—except for the little spin in “palatable.”

Cheers, Jack Fritscher, founding San Francisco editor in chief of Drummer

http://www.DrummerArchives.com

I’m still not sure “palatable” is the right word for the point I was trying to make, but I assure you it wasn’t a matter of disapproval by any means