[Repposted from an old ID article from 28 March, 2017]

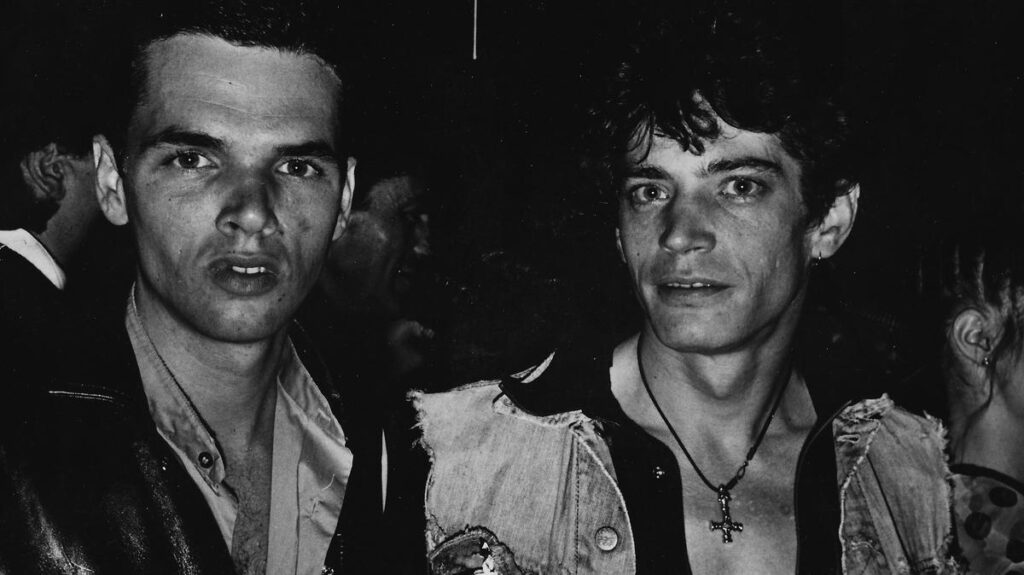

As he debuts photographs of the provocative artist made during a late night in 1979, Leatherdale shares his memories of Mapplethorpe and downtown New York.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, many considered New York to be a city in decline (the Council for Public Safety produced a controversial pamphlet aimed at keeping tourists out of town entirely). Yet the era produced a generation of renegade New York artists. As hip-hop emerged in the Bronx, the burgeoning punk movement cross-pollinated with the avant-garde nightlife scene downtown. In this post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS period, members of NYC’s queer community were breaking new ground not simply in the art they made, but also with the lives they lived. The work and ideas produced in this era still profoundly shape New York today.

Canadian photographer Marcus Leatherdale captured much of this experimental energy — staging his first exhibitions at Club 57 and Danceteria, and later photographing Keith Haring and Leigh Bowery for his Hidden Identities series. Published in the original Details, Leatherdale’s arresting black-and-white photographs show their subjects with obscured faces, but hint at their iconic identities through their style and stature. Before any of this work came the never-before-seen portraits Leatherdale is now showing at New York City’s Roman Zangief Photos — color photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe made in 1979.

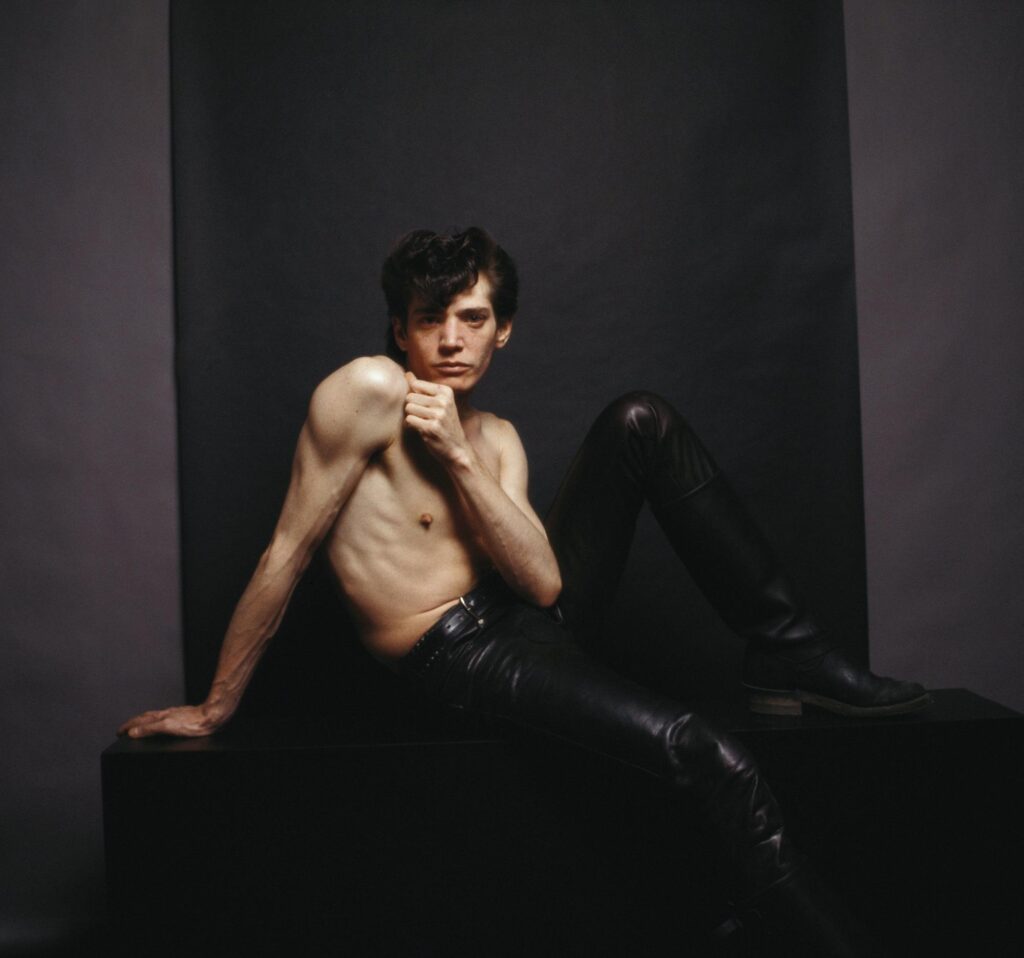

Returning to Mapplethorpe’s studio after a late night, Leatherdale began to photograph his then-boyfriend. Mapplethorpe appears the way most of us know him — confident, and in perfectly fitted leather. But Leatherdale also brings out a relaxed, natural energy not often found in Mapplethorpe’s own classical self-portraits. The pair’s intimacy and trust make the photographs feel fresh. Last year, Leatherdale’s biographer, Martin Belk, discovered the images while conducting research into the photographer’s archives. We caught up with Leatherdale to learn more about the forgotten portraits.

Tell me about your first time meeting Robert. What were your first impressions?

I first met Robert in San Francisco, when I was a photography major at San Francisco Art Institute. He was having two exhibitions: one of his portraits and one of his sex photographs. Several people, including teachers, suggested that I go and see his photographs, as they thought our work was somewhat similar. I had no idea who he was, except that I was a huge fan of Patti Smith at the time. When I was told that he shot the Horses album cover for Patti, I was intrigued. I went alone to the gallery to see his portrait show, and actually didn’t really get his work at first. Our mutual friend in San Francisco, Peter Berlin, invited me to go to Robert’s opening of sex photos with him. It was at the opening that Peter introduced me to him. Of course [Robert] was holding court and was quite busy talking to all his admirers, but when I was leaving, he stopped me and invited me to have dinner with him the following night.

The next evening, I picked him up in my MGA Roadster. He was quiet and reserved, and we talked mostly about photography. Peter turned up after dinner. They were going out to some bars, but I bowed out as I was leaving the next morning for Arizona with my good friend Gail. She had a baby blue Cutlass Supreme and we were going to try out our new SX70 Polaroid cameras by touring all the miniature golf courses in the desert. Robert was somewhat put off that I had other plans. I told him that I was planning to relocate to NYC that summer after graduation, and he graciously offered me to have me stay at his place.

I didn’t take the invitation that seriously as we had only just met. But when I returned from my road trip, there was a postcard from Robert with his phone number and address in NYC, inviting me again to come and stay at his loft. So when I arrived a month later, I called Robert and stayed with him until I could find my own apartment. He was very trusting. He went to Amsterdam for a month and just gave me the keys to his loft.

You managed Robert’s studio for a few months too. What did that experience entail?

I would try to keep everything organized, set up his prints for exhibitions, then we would usually meet up with Sam Wagstaff for lunch and finish up back at the studio. It was not that hectic back then. He had a darkroom assistant at the time as well.

Robert was determined to be a star, at all costs. So when I started to be known for my photography, tension grew. We were both photographing in NYC at the same time, and often the same people, so there were comparisons and he could not handle that. Of course, Robert was the more accomplished artist, however we also worked on parallel levels that many did not realize. We both photographed [bodybuilder] Lisa Lyon, who I actually introduced Robert to through a mutual friend, Marcia Resnick. Robert did not use strobe lighting when I met him, only tungsten or daylight. He had amazing equipment that Sam bought him, but was afraid of being electrically shocked. So I got him used to using bounced strobe lighting that I was learning to use as well at SVA. We were artistic comrades, at first, until I got recognition. But in all fairness, NYC is place where everyone is very career-oriented. I too was very ambitious, but not competitive.

In addition to Robert, you captured so many important people in the city’s nightlife and creative scenes throughout the 1980s.

I photographed within the in-crowd of the downtown scene. But without realizing it at the time, I archived an era that was to be extinct in 20 years. We thought we would be 20-something forever. I have moved into a new tribal life — in India — that is also evaporating into extinction. Only this time, I am aware of it.

There’s been much renewed interest in Robert’s life and work: the HBO documentary, the Raf Simons collection, and Just Kids is being developed into a TV series. Why do you think this is happening now?

There is much renewed interest in Robert’s life and work, and I am very happy for him. However, I did not like the documentary film at all; it was a gross misrepresentation of Robert’s life. But then again, history is forever being rewritten by people who were not there, and did not know the real dynamics of Robert’s desires and ambitions. Yes, Robert wanted to be famous and yes, he was a perfectionist in everything he did. He was very intense and driven, but not the shark that was implied in the film. Robert was self-centered and ambitious, but he was also a kind and generous guy who loved to joke and gossip. At times, he was almost childlike in his pleasures. We once traveled together to Canada to visit my parents at the family lake house, and he did nothing but fish off the dock all day, just like a little boy.

When you look at these images, what do you see that others may not?

These portraits of Robert are special and unique in that they are the only color images that I ever shot, as I have always worked in black and white. I sincerely hope they give a glimpse of my best friend, “Bone Face” — that boy who was content to just fish on the dock.