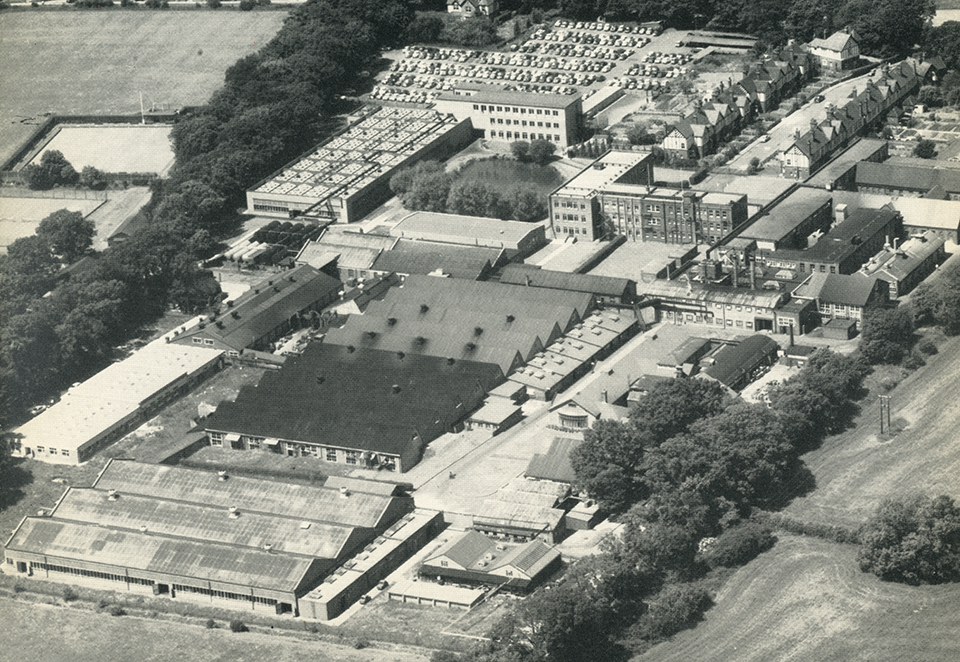

When we show material from Monotype’s archive in the UK, I like to include photos of the Monotype Works, the company’s cluster of factory buildings in Salfords, Surrey. Seeing an aerial view of the Works and a few glimpses inside some of the factory buildings gives a real sense of scale to the operation. It took a lot of people, space, material and equipment to make all those machines and all that type, and it can be tricky for people who’ve only interacted with digital type to really appreciate what went into creating the typefaces that carry over from the days of metal type.

Another point that I like to make is that the Monotype Works in Salfords was just one location out of many that were producing type (and type-making machines). Even if you look at the companies that are part of Monotype today, there were (at one time or another) the Works in Salfords, a plant in Scotland, a plant in Frankfurt, plus Lanston Monotype in Philadelphia, and Linotype’s plants in Brooklyn, England, and Germany. That’s an awful lot of activity and infrastructure. And it’s only one slice of the industry.

Even traditional foundries (as opposed to companies like Linotype and Monotype who made machines that letter people produce their own type) were huge. Have a look the Caslon Letter Foundry in London around 1902, or the Haas Type Foundry in Switzerland in 1950, or even a printing operation that made its own hot-metal type like the US Government Printing Office.

When we talk about the type industry today, we’re talking about software and design companies, from tiny one-person studios to (at Monotype’s end of the scale) a few hundred people. What has disappeared is a proper industry of machines and factories and scores of people. Physical type is a small-scale craft these days, which is pretty great in some ways, but a sad loss in others.