Now that we’ve started drawing and sketching for our practical work, I’ve been spending more and more time thinking about the kinds of forms that might work well for the problems I’ve been talking about so far. In many ways, it’s a very open-ended question: it’s not a unique problem to want clarity and legibility in type for dense text situations that may not be produced well. For the kind of technical publications I’m targeting, a certain kind of “classical” or “traditional” feeling would probably be received well, but I’m determined to sneak in as many technical adaptations (addressing issues of reproduction quality, optical sizes ranging from titles down to elaborate superiors and inferiors, legibility of individual letters as well as words) as I can.

As I devoured material on all sorts (hah! No geeky pun intended, I swear) of type and type history, I ran across a notion over and over again about the need for open counter spaces, especially at smaller sizes, as a key factor of legibility. Reading Fred Smeijers’s Counterpunch got me thinking about how punchcutters dealt with internal shapes as a discrete design solution which could be shared among glyphs and adapted as needed at a later stage of the production as a punch. It was a way of building a letter from the inside out, suggesting a relationship between outer contours and inner ones that was sympathetic, but not necessarily tied together any more than it needed to be. The details of the outer contours could bear the burden of overall style while the inner contours bear the burden of keeping the shapes clear and defined. Of course, they work together to produce the overall effect, but they don’t necessarily have to address the same problems in the same ways.

I kept going back to Dwiggins as I thought more about this sneaky trick of mixing inner and outer shapes, appearance and utility, and — in his use of stencils to build sets of trial characters out of recurring shapes — laying out the fundamental parts first in order to set up the patterns in a given design. I was noticing certain qualities in his types that all snapped together and made sense when I read about his “M Formula” in Gerard’s Quaerendo article, a brilliant notion of using optical illusions that somehow zipped past me during Typecon’s “DwigFest” this past summer.

It’s clear that plenty of type design harkens back to Dwiggins’ ideas: I’ve found people like Gerard, Cyrus Highsmith, and Christian Schwartz taking cues form his work, not to mention the various revivals of his types. I haven’t stumbled across anyone else connecting his optical tricks to those of punchcutters, even though they were constructing letters part by part in a way all their own.

So I’m thinking I may be onto something I can look into for my essay, while I keep looking into it for my practical work. I’d like to inspect some punches and matrices and look at their details more closely, and trace how this idea of separate development of inner and outer contour shapes has made its way through to digital types today, considering what technical and legibility issues have been encountered along the way. It could be a vast topic, probably, but it could be useful to at least investigate some fundamental patterns to it.

In the end, Dwiggins realized the stencil didn’t work because it lacked any livliness of form. The letters conformed to much an there was not uniqueness. However, I don’t think he ever left the thought behind and had he lived longer I think he might have really truly enjoyed playing with different parts on a computer to experiment with the idea all over again.

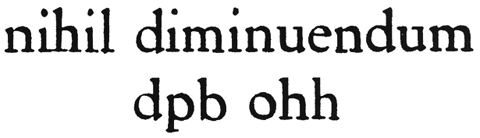

The M Formula and the stencils are really two separate things, as you know. But if you could find a way to incorporate the meat of the M Formula into the stencil idea that might be interesting. However, I still think you’d have too much conformity in shape. If you look at the image you post you can see what I mean. Having so much repetition makes the shapes sparkle too much. IMHO

The stencil idea is mostly interesting as a way to lay down some repeating shapes, which is comforting to someone who’s freaking out over the idea of drawing out a whole set of letters for the first time. The stencils, in effect, are a skeleton, and the real design would come out of working out how more fleshed out details can bring life to that skeleton.

Yes, of course, that is very true. I wasn’t saying not to use it, I was just pointing out what I see when I think of Dwiggins’ stencil experiments.