One day when I was walking through the cafeteria, I heard Mike Malone call me a faggot under his breath as I passed by his table. I handled this, as I always handled slurs like that, by laughing to myself and thinking, “not only is he wrong, but he wouldn’t know anyway. He just thinks I’m a fag because I’m different.”

One day when I was walking through the cafeteria, I heard Mike Malone call me a faggot under his breath as I passed by his table. I handled this, as I always handled slurs like that, by laughing to myself and thinking, “not only is he wrong, but he wouldn’t know anyway. He just thinks I’m a fag because I’m different.”

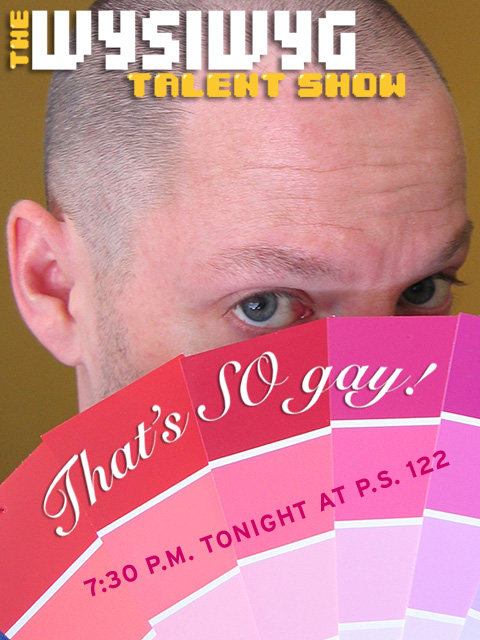

Well, Mike Malone may have been a dick and funny-looking but he was also right. I was deeply in denial about the fairy dust I had in me. When I was a little kid, I was basically a big sissy but I had no idea there was anything wrong with the way I went about my business. When I was a teenager, I wasn’t as much of an outright sissy, but only because I was a lot more conscious of how I behaved. By then I understood the stigma of not being one of the guys and deep-down, even years before I could admit or even articulate it, I knew that those occasional slurs weren’t off-base. In my conscious mind, though, I wasn’t a homo, I was New Wave. I was sassy, not sissy.

(A few years later, when I was first runner-up in Sassy’s “Sassiest Boy In America” contest, I insisted this was proof that I was right all along. I still had a few epiphanies waiting to happen, clearly.)

When I was a little kid, I didn’t worry so much about whether or not little boys were supposed to go swimming in their Aquaman underoos or spin around trying to turn into Wonder Woman. These were just the ways my imagination played itself out. When you’re young enough you can be oblivious to what’s expected of you, so it never occurred to me that there was anything wrong with my intense desire to be the Bionic Woman. Sure I could run around playing tag, but it was so much more fun to run around pretending to be a super-strong undercover agent with flowing blond hair who, if she wanted to, could beat the crap out of any mean kids that made fun of her. Jaime Summers and Wonder Woman were glamorous and strong, and even they always got to pretend to be other people when they were on a case. Sure, Steve Austin did the same stuff, but he was so squinty and serious all the time!

It wasn’t even that I wanted to be a woman I just wanted to be someone more exciting. Spider-Man or Aquaman or the superheroes I made up myself also got to wear cool costumes and do excellent things like fly or breathe underwater or go into outer space. I aspired to stuff with more pizazz and fewer stupid rules than little league or cub scouts or basketball. They were boring, and when I gave in and tried to do them, I knew that (1) I was spastic, and (2) I had a whole lot more fun when I could tune out the dreariness of the real world and act out things the way I wanted them to be.

For instance, I once turned my bookcase into a doll-sized office building for my action figures. I designed rooms out of old shoeboxes jazzed up with crayon-drawn decorations and furniture made out of Legos and styrofoam packing pieces. In this lavishly furnished high-rise I used the various Princess Leia figures as one of my characters a super-powered lady private eye who fought crime and changed her clothes a lot. She had a Fisher-Price boyfriend who was good-looking and spunky, but not quite as spectacular as she was. He had to be rescued a lot, but he loved her for it.

I wanted things to be more exotic and less conventional than the other boys my age generally wanted. They were the ones always harping on what you were supposed to do in this game or that thing, and I thought they were dull. Why did I even play with them in the first place? I guess it was gratifying to go with the flow and not feel like an outcast. Somehow or another, I learned from them that it was definitely not cool to try and be the Bionic Woman, but it was still OK to be Luke Skywalker. Fine, I could work with that a Jedi could be adventurous but still pull off being kind of sensitive.

As I got older, I kept learning those ambiguous rules about how far I could follow my gut instincts. I could obsess over Duran Duran or Francis Ford Coppola’s The Outsiders, but I could really only share my enthusiasm with girls that I knew. I could commit the entire soundtrack of Grease to memory, as long as I never let on that I wanted a greaser in a leather jacket to sing me a love song. I could cover the walls of my room with magazine pages like a 14-year-old girl, but as a fourteen-year-old guy I had to make it very clear that it was about the music, not about my fascination with that picture of Billy Idol wearing a rubber bikini brief on the cover of Rolling Stone. I could be a bit of a dandy with my thrift-store wardrobe, my Vans, and my asymmetrical haircut, but I could only attribute it to the music I liked and the crowd I hung out with I could definitely not consider the fact that I wanted to make out with skater boys, not be one. I could be myself, and I could be different from the other guys, but I could only go so far before I drew too much of the wrong kind of attention. It was a point of pride to be ostracized for being quirky, New Wave, and bookish, but in an all-boys Jesuit prep school, you definitely did not want to dazzle too much and cross that line into faggotry.

The worst part of that whole, long process of testing the boundaries of what I could get away with and what I couldn’t is that all I really thought about were the boundaries, not where I might really fall outside of them. I cultivated a certain way of being unconventional for years before it dawned on me that I really was gay, and that being gay was the thing I had been trying to avoid all that time. And really, it was the least interesting quirk of them all. Once it dawned on me, it made perfect sense and wasn’t such a big deal. Bring on the ass-fucking!

As it turned out, being gay wasn’t as big a deal as learning how to do what I wanted without standing out more than I cared to. It’s a habit that’s backfired, because now I’m so nonchalant about being queer but so self-conscious about being considered kind of ordinary. I’ve developed a lifelong habit of being a little weird for my environment without standing out too much. A certain degree of eccentricity is very comfortable for me, because I don’t have to pass at being something I’m not, nor do I have to deal with the hassles of being all that different. These days, though, I could probably be a whole lot more fun if I fully embraced my inner sissy, but now I don’t really feel like it. It’d be too conventional.