My first reaction to the death of my older brother Bobby when I was thirteen was one of sheer confusion. I remember when I found my sister sitting and crying on the steps to our house, and when she explained that the police had found Bobby’s body in a patch of woods near our house, I just wondered how I was supposed to react. When I walked into the house, I encountered a room full of family members either weeping or comforting those who were. A lot of the details of the next few days are pretty fuzzy, but I still have a few impressions of how I dealt with the situation.

The confusion didn’t really go away. I know that on a gut level, I wasn’t that sad about what had happened. I wasn’t close with my brother — he scared and aggravated me more than anything else. He had a lot of problems, and even at the age I was then, I figured out that he couldn’t go on forever if he kept treating himself the way he did. I could tell, however, that I was expected to be upset, even though I was more numb than anything else.

I can recall from that same morning when we learned that Bobby had killed himself that my mother and my Aunt Lee followed me into my room to comfort me. I burst out into tears, but I’m was pretty sure that I was more upset about the people in the next room than about the less concrete idea that my brother was gone. The despair in the living room had hit me like a brick when I entered the house, and I guess I went to my room to try and hide from it. When Mom and Aunt Lee in effect forced me to acknowledge the situation, I cried because I was confused about how to react, and because everyone I looked to for support when I was sad was pretty sad themselves.

I remember feeling numb and awkward during the wakes and the funeral, too. I was bugged by all these people offering me sympathy when I didn’t really feel the need for it. I wonder now if I really faked mourning well, or if everyone was too distracted to notice that I wasn’t grieving like everyone else.

For a long time, the hardest part was always trying to explain the situation accurately. I wasn’t comfortable talking about my brother’s death, because people always reacted so strongly — moreso than I ever did. I wasn’t comfortable with the kind of empathic scrutiny that people try to offer the bereaved, because I didn’t want to be found out.

Now, it’s years later and I have a very different perspective on the situation. As I grew older, I discovered what a profound influence my brother Bobby had on me — he, with a little help from my other siblings, turned me into the goody-two-shoes I am today. I basically used him as a model of what not to do with my life — how not to treat my parents, the value of staying away from drugs and alcohol, the importance of hard work. Whenever I faced a tough peer pressure situation, I usually stuck to my guns, and freely offered the explanation that I’d already seen what a little bit of experimentation could lead to.

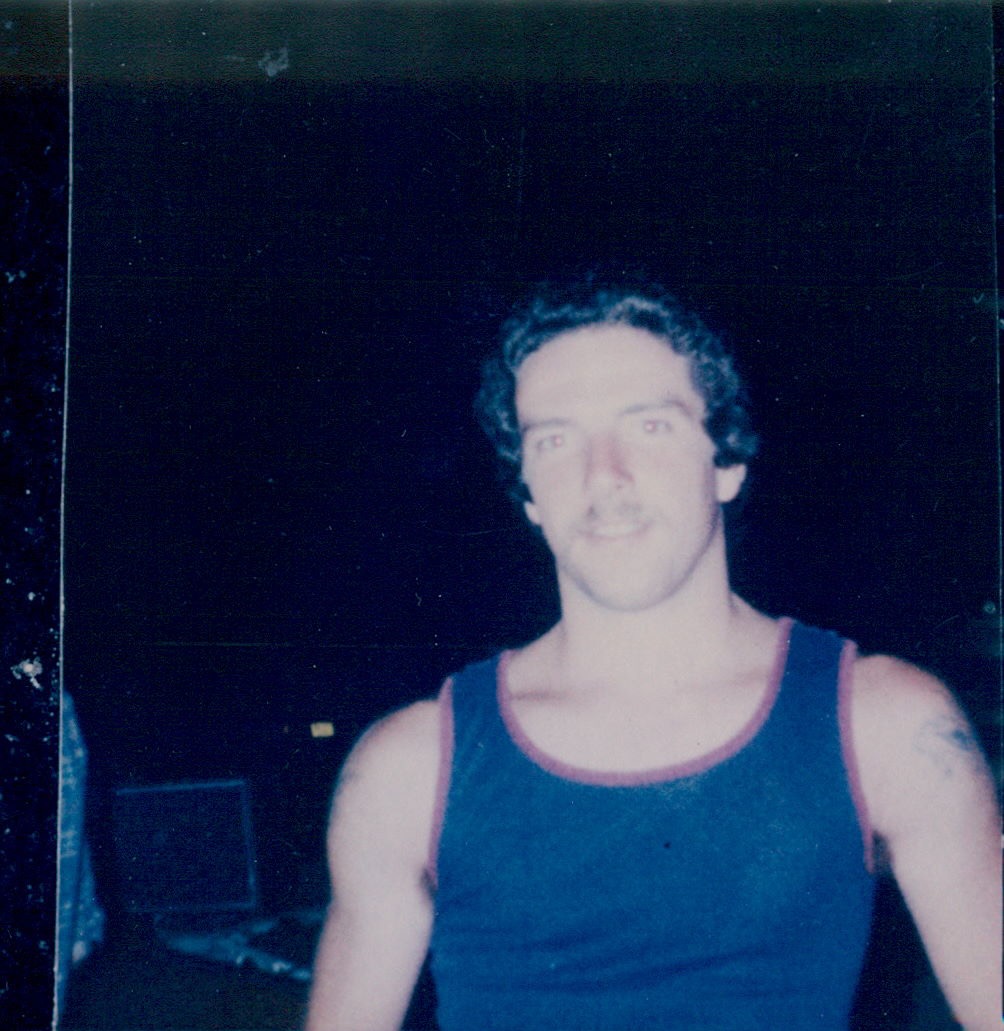

All that time, though, while I pondered the implications of my brother’s life, I still didn’t really feel the loss of his death. I could appreciate the tragedy from an objective sense, but it never had much of an effect. The closest I ever felt to grief for most of the last ten years has been during the times when I realized that I had taken on superficial qualities of my brother’s — such as a certain haircut or a piece of clothing like he used to wear — but I never felt grief so much as a vague but profound discomfort.

Last year, though, I felt my first real pang of grief and loss, the first real understanding of how awful it was that he was so upset with his life that he ran away from home and shot himself in the woods. By this point I had accepted the grim possibility that I might be prone to depression, and that depression may have played a big part in the outlook of my brother. I was at work one day, and it occurred to me that it was about the time of year when Bobby died. Then I realized that I was now the same age he was when he died. It dawned on me that I had gotten as far as he had, and I was okay, even if times were tough sometimes. I realized how awful it was that I was never going to know my brother as a person — we would never be peers. He had always been an almost mythical example of behavior to me, a bad role model. Now he wasn’t older and stupider and a memory; he was a young guy like me who couldn’t figure out his life and couldn’t see that he had a lot of people who would have been willing to help him do it, a guy who made some bad choices but usually tried to be a decent character, but wasn’t going to live to know that people appreciated it. Suddenly, I felt a huge loss, and the first real pangs of sorrow about what had happened years before. I knew what grief felt like for me, and it wasn’t the violent, demonstrative kind of wailing I’d seen for years in movies and TV, it just ached and felt empty.